Reviewer First Pull Requests

Pull requests continue to be the primary mechanism by which we collaborate and contribute code. Despite this we often will put as little effort as possible into creating PRs. I’d like to convince you that even a small investment in improving them pays over-sized dividends to the project and your team members.

Table of Contents

- Background

- Overview

- Guidelines

- Commits

- Tooling

- About Commit Mistakes

- Receiving Feedback

- Merge or Squash Merge?

- Appendix: Commit Order Reviews

Background

I’ll start by admitting that because the PR is frequently at the very end of a development effort that we should pay respect to the mental exhaustion present. A project spike will start with a mountain of known unknowns, and some unknown unknowns as well, all of which an IC will be accountable for, in addition to writing code that is maintainable, tested, and covers edge cases. It can be exhausting and therefore understandable that we would feel the impulse to create the PR as quickly as possible to get it over the finish line. I hope you’ll agree that by the end of this post that spending a bit more effort to create a better PR is worth it, and is probably not as much effort as you might think.

Let’s start with the perspective of the reviewer. Everyone is familiar with this scenario: you get a notification about a new PR you need to review. You open the PR and see that the title of the PR is a JIRA ticket. The description of the PR is blank. You find the JIRA ticket and read it to get some context before continuing. Going back to the PR, you see about forty commits, many of which are things like “migration” or “wtf please work” or worse. Given this you click the “Files changed” tab and see that there are 5k lines of code changed, across 30 files. Resigned to your fate, you then try to understand this large changeset all at once. Because it’s incredibly difficult to do so and because you are also under pressure to deliver your own changesets, you end up reviewing it at the surface level, leaving style feedback and perhaps some more nuanced commentary for the parts you are able to understand more easily.

This is clearly not the experience we want.

As the creator of the PR, you are hoping to merge it. But past that, you also want your teammates to let you know of things that you may not have considered, or why this particular algorithm you’ve employed may have negative effects on the backend APIs it eventually calls. Style nits are OK but avoiding an incident by pointing out an unhandled edge case is much better.

The reviewers only have so much time to devote to your PR. If that time is largely spent being mystified about the changeset, that is time that they are not spending giving you the quality feedback you should be hoping for. The time a reviewer spends on any particular PR is then multiplied by the number of people that end up reviewing it.

The value of a well documented PR lives on past just the initial review, too. If this is a service running in production, someone else on-call that didn’t review the PR may need to refer back to it when there’s an outage and they are trying to understand what happened. If this is an OSS project, people may want to review the PRs that land in the next release to better understand how the project is changing.

Time spent creating a better PR pays dividends many times over.

Reviewer First Pull Requests (RFPRs) Overview

Reviewer First Pull Requests (RFPRs) are a prescriptive approach to building better PRs that are easier to review. One time at Mesosphere after I pushed a PR that was hard to review, Kevin Klues introduced me to his “Reviewer-First” methodology and I’ve been promoting it ever since.

At the heart of RFPRs is the concept that PRs, like a book, should tell a story.

When reading a book, you typically know what it’s about before you start because you’ve read the intro on the back. You start at the first chapter, and continue reading until the end. Even if the book was particularly long or complex, the chapters were structured in a way to guide you through the story that the author wanted to tell.

RFPRs operate under the same principle. A reviewer should be able to open the PR and read the description to get a good idea for what the PR is addressing and what to expect inside. RFPRs are structured so that they can be reviewed commit-by-commit, in order, leaving feedback as they go.

Large or complex PRs are made more approachable if the author guides the reviewers.

RFPR Guidelines

Following are guidelines for creating RFPRs. Afterwards we’ll discuss some tooling that will make following the guidelines much easier.

PR titles

PR titles should describe what the PR accomplishes.

Examples of good PR titles:

- [CONTROL_42] Expose gRPC endpoints for all controlplane APIs.

- kafka: Create new topic for user events and enable mirrormaker for all regions.

- Modify CMS domain models to use composition instead of inheritance.

PR titles which should be avoided:

- [CONTROL_42] (just a JIRA ticket number)

- fix bug

- (nothing)

Imagine that you are trying to find a particular PR on GitHub during an incident. The PR title should be descriptive enough so that it can be easily identified.

PR descriptions

The PR description sets the stage for the reviewer. Since they are going to review the PR commit-by-commit, the description should give them as much context as possible before they start. Assume that the reviewer does not have the context that you do.

The description should roughly include these components:

- Links to tickets or other prior art.

- Overview of the problem or business goal.

- Description of your approach.

- Callouts to any parts which are complex or about which you are hoping for extra feedback.

- Edge cases and risks.

It’s worth noting that PRs which are small in scope will have a correspondingly smaller PR description. PRs which are large or complex will have a larger PR description. This is largely subjective, and at first I think it might feel like it’s unnecessary work, but that is temporary. In fact I’ve found that by writing a detailed description, I will sometimes remember things I had forgotten to address during development. By writing the description for the reviewer this causes you to think about the things that the reviewer would probably have questions about. Anything you catch at this phase is a major win, as it is a short amount of time compared to the revisions to the PR which would otherwise follow.

Code snippets (for example, to showcase a new interface you are adding) are often really helpful in the description.

Commits

The reviewer should expect to be able to review your PR in commit order if they choose. What order should the commits be in and what should the commits contain? Remember that we are assuming that the reviewer is coming in fresh and probably does not have the familiarity with the code that you do.

In general I try to isolate what I consider to be “high value” and “low value” changes in separate commits. A high value commit would be something like adding a new trait, or implementing that trait for a number of domain models. Low value commits would be things like formatting, or code imports. To make it as easy as possible on the reviewer, allow them to briefly consider low value changes and spend more time on the high value changes.

Do not mix high value and low value changes in the same commits.

Since the reviewer is reading in commit order, we should also strive to limit the scope of any particular commit. If your PR is adding and implementing five interfaces to all of the domain models, a reasonable approach would be to have each interface, and the implementation of that interface, be in its own commit. If you’re sweating now because you’re not comfortable with Git, don’t worry – we’ll talk later about tools you can use to build these kinds of commits.

Guidelines for good commits:

- Commits should be limited in scope.

- Do not mix high value and low value concerns in the same commit.

- Commit titles should be a full sentence that describes an action.

- Commit descriptions should discuss that commit’s changes as necessary.

Here’s an example of a medium-sized PR that follows these guidelines:

Set ECS Attribute to indicate health of ledger latency

JIRA: F8N-365

# Overview

This is the first step of a longer term goal to be able to control the behavior of ECS task

placement for tasks which rely on this database. The idea is that if the task requires a healthy

ledger latency we can avoid placing it on a node which is behind.

# Approach

This PR adds some new behavior to the reflectors. The reflectors will start a ledger latency

monitor when they start. This monitor will periodically look at the ledger latency as reported

by the db client. If below a max threshold, it will ensure that the container instance on which

it runs has an ECS attribute to indicate the ledger has fallen behind.

# Next Steps

After this is deployed and working we should spot check new instances to ensure that they are

not marked as 'healthy' if they are still working on updating the ledger. Once we are confident

in this, we can then update our deployment tooling to lean on this new attribute.

The commits on this PR try to follow RFPR guidelines. Notice how low value and high value changes are isolated:

* Move loop helper code to pkg/loop.

* Add ECS dependencies.

* Update executive interface mock.

* Create an ECSClient interface and generate mock.

* Create EcsMetada type to unmarshal ECS metadata.

* Create ledger monitor to set ECS 'unhealthy' attribute when falling behind.

* Add functional options for the Monitor.

* Update reflector config to also compose ledger health config.

* Add tests to verify attribute is set correctly using a mocked ECS environment.

Example of what I consider to be a reasonable commit within this PR.

Create ledger monitor to set ECS 'unhealthy' attribute when falling behind.

The monitor follows the pattern that the other types use, where a Start(ctx) method blocks, and

only exits when the context is canceled.

It follows this high level logic:

* Every time the *time.Ticker ticks:

* get the ledger latency from the db

* compare this value to threshold

* if latency is OK, set a 'healthy' attr

* else set 'unhealthy' attr

It keepds the last known successful ECS attr set in a local var so that it doesn't set the attr

on each tick. The variable is a *bool because we need three states:

1. unknown state of ECS attr

2. 'healthy'

3. 'unhealthy'

These are the kinds of PRs I’m thankful to get notified about. I might spend on average 15-30m extra to create PRs using these guidelines, but it saves many hours across the reviewers assigned to it, and the quality of feedback you get on your RFPR will invariably be higher.

Tooling

Much of RFPRs ends up being a writing exercise – writing your PR title, PR description, commit titles, commit descriptions, with the reviewer in mind. But a large part of RFPRs involves commit discipline. If you’re like me, you really only know what the changeset is going to look like after you finish making all of your changes. As I approach the finish line, my feature branch has tens if not hundreds of garbage commits.

In fact I have a ci (checkin) script that enables these garbage commits. I love it:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -euo pipefail

msg="${*:-wip}"

git add -A

git commit -m "${msg}"

I use this constantly and so my feature branch is littered with wip commits. These are my

breadcrumbs that enable to me to “checkpoint” my progress in a way that doesn’t take me out of the

flow. They also let me back out more granular changes – maybe I wanted to see if a particular change

made sense. I ci before I start, and if I hate it, it’s easy for me to throw away that change

without risk of throwing away what came before it.

A branch that looks like this is clearly not RFPR-ready. How then do we go from a feature branch

full of wip comments to something that is a RFPR? My strategy, which works for me, is to wait

until the very end to restructure my commits. The primary way I do this is by using git reset and

lazygit. Note that there are a lot of tools like this, and I encourage you to explore what is

right for you.

git reset

Your feature branch (e.g. collin/ecs-attr) is meant to eventually merge into a base branch, which

is often origin/main. Our goal is to 1) keep all of our changes and 2) craft custom commits that

tell the story of our RFPR.

If you’re not familiar with git reset, it probably sounds scary, but it’s not actually destructive

in the way it sounds. Using git reset --hard IS destructive and should be used with care.git

reset will point your branch to whatever you reset it to, and any changes on your branch will be

moved into the working tree. The effect is that it is as-if you just created your feature branch on

top of origin/main and then made all of those changes. From there we can start building our

commits.

- (on

collin/ecs-attr):git fetch; git merge origin/main - (on

collin/ecs-attr):git reset origin/main - Build commits

All of our changes have now been unstaged and it is up to us to build our commits.

I like to start with the lightweight concerns. If you have some documentation changes, add those files into a commit. If your feature required modifying some other things to support it, adding commits for those updates would be reasonable. After I’m done with the prerequisites, I then add commits for the changes which are at the heart of my PR. Following those are typically commits which address testing. Finally, I usually save most of my formatting changes for one commit near the end which reviewers can spend minimal time on since it should be a no-op.

Some commits are naturally scoped to whole files. For example, if you updated the README, then

adding the whole README file (git add [file]) and then making a commit is reasonable.

If your PR was introducing five new interfaces and implementations across your domain models, you’d

probably want each of those to be its own commit, but the model files they modify are the same ones.

You need some way to only add parts of each model file for the commit that adds one of the

interfaces. Similarly, how do you isolate formatting changes when those changes touch most of the

files? lazygit!

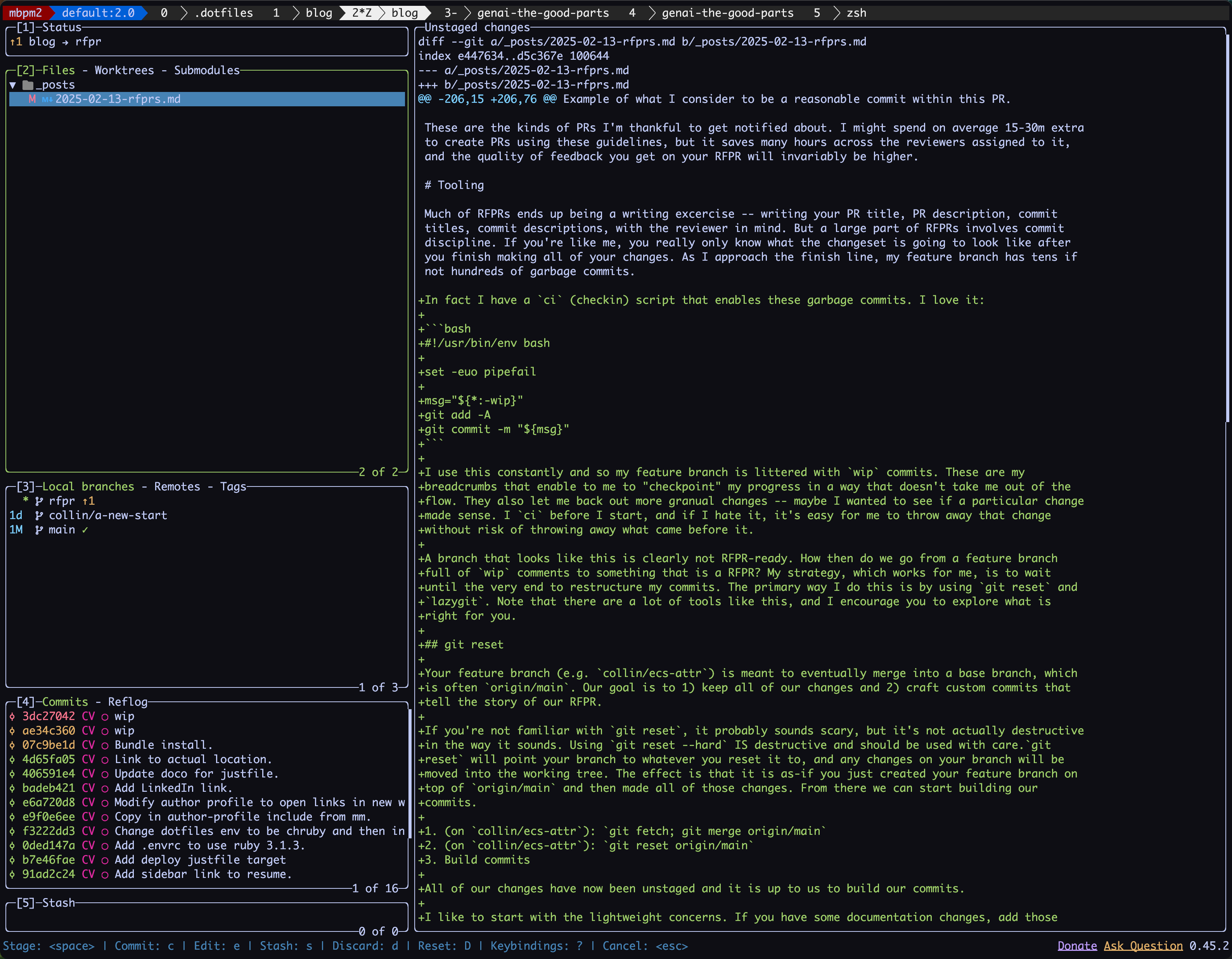

lazygit

Lazygit is a terminal UI (TUI) that enables you to

easily perform Git actions that would otherwise be more difficult. This is a screenshot of my blog

repo which I use for this site:

It’s organized into different pages, each of which has a different responsibility:

- changed files

- branches and remotes

- commit list

- stash

- changes diff

Using this interface, I will frequently:

- build commits for a RFPR after a

git resetto the base branch. - add individual lines across multiple files into a new or existing commit.

- reorder commits on a feature branch.

- amend a commit with a particular change.

- take a change out of a commit and create a new commit from it.

- … and much more

This post does not intend to be a tutorial on how to use lazygit. You should start with the

Tutorials to get a sense

for it. Getting a hang of the keybinds takes a short while, and then you can configure it to your

liking.

Believe me when I say that using a tool like this gives you a lot of power. So much so that when I

create a RFPR, I spend more time on writing the documentation for it than actually building the

commits using lazygit – it’s that good.

About Commit Mistakes

The above approach is really helpful in ensuring that reviewers do not spend time giving feedback for changes that will never merge. Imagine you have a PR with 10 changes. The 5th commit introduces a bug which is then fixed in the 8th commit. Assuming that the reviewer will be reviewing in commit order, they will likely spend time giving feedback about the bug in the 5th commit, only to become irritated that they spent that time unnecessarily.

Backing out all of your changes and then building the commits before the PR is created avoids this

problem entirely. Performing a git reset to origin/main will in effect merge your changes

together, only leaving the correct, bug-free diff.

If after you’ve created your commits you notice a bug in the 5th commit, you definitely do not need

to start all over. You can fix the bug in the working tree and then in lazygit navigate to the

commit where the bug is. Hitting A will amend the selected commit with your changes. There are a

lot of nice-to-haves like this in lazygit.

Receiving Feedback

Once you’ve posted the RFPR, gotten feedback, and need to make followup commits, those commits should also be RFPR commits. Other people will come back later and read through them and we should also respect their time.

I would highly recommend not rebasing or rewriting commits after you start getting feedback. The

reason for this is that reordering or amending commits ends up creating new commits under the hood

(even if lazygit made it super easy to do so). Because reviewers will leave feedback on each

commit during the initial review, if you rewrite that commit as a followup and force push, the

feedback they left becomes orphaned and out of context because that commit no longer exists.

For that reason, it’s better to push new commits when addressing feedback, even if those changes would normally be structured differently if you were creating the RFPR from scratch.

Merge or Squash Merge?

Once you’ve gotten your approvals and are ready to merge, what then about how to merge? You can either merge normally or use a squash merge. I don’t think there’s a clear answer on this. Perhaps we’ll get one when the tabs vs spaces debate gets settled. I’m happy though to share how I view this decision.

If we step back and consider a team that typically creates PRs that would not be considered RFPRs,

in this case squash merge is probably the right choice. There’s little value in maintaining commit

history in this case, and it makes the commit history a bit easier to review. You simply look at the

commits on main which each represent a complete changeset.

Otherwise, I think the choice comes down to the git expertise of the team. If everyone has an above average comfort level with git mechanics, it probably makes sense to consider using merge commits. It can be easier to find the cause of a particular regression and it makes some other workflows a bit easier.

I personally prefer to use merge commits but have no issue with using squash merges if the rest of the team wants to. Like many things of this nature, “It depends”. It’s more important to have everyone on the team committed to the approach, whatever it is.

Note that if your team is using squash merges, there’s no wasted effort in spending the time to

create the RFPR. Even though your commits will end squashed on main they will still be preserved

in the PR, and the reviewers will still appreciate that you respect their time and effort spent to

review it.

Conclusion

I hope I’ve been able to convince you that RFPRs are worth the effort. Your teammates will thank you for this and perhaps you can convince them to also write their own RFPRs.

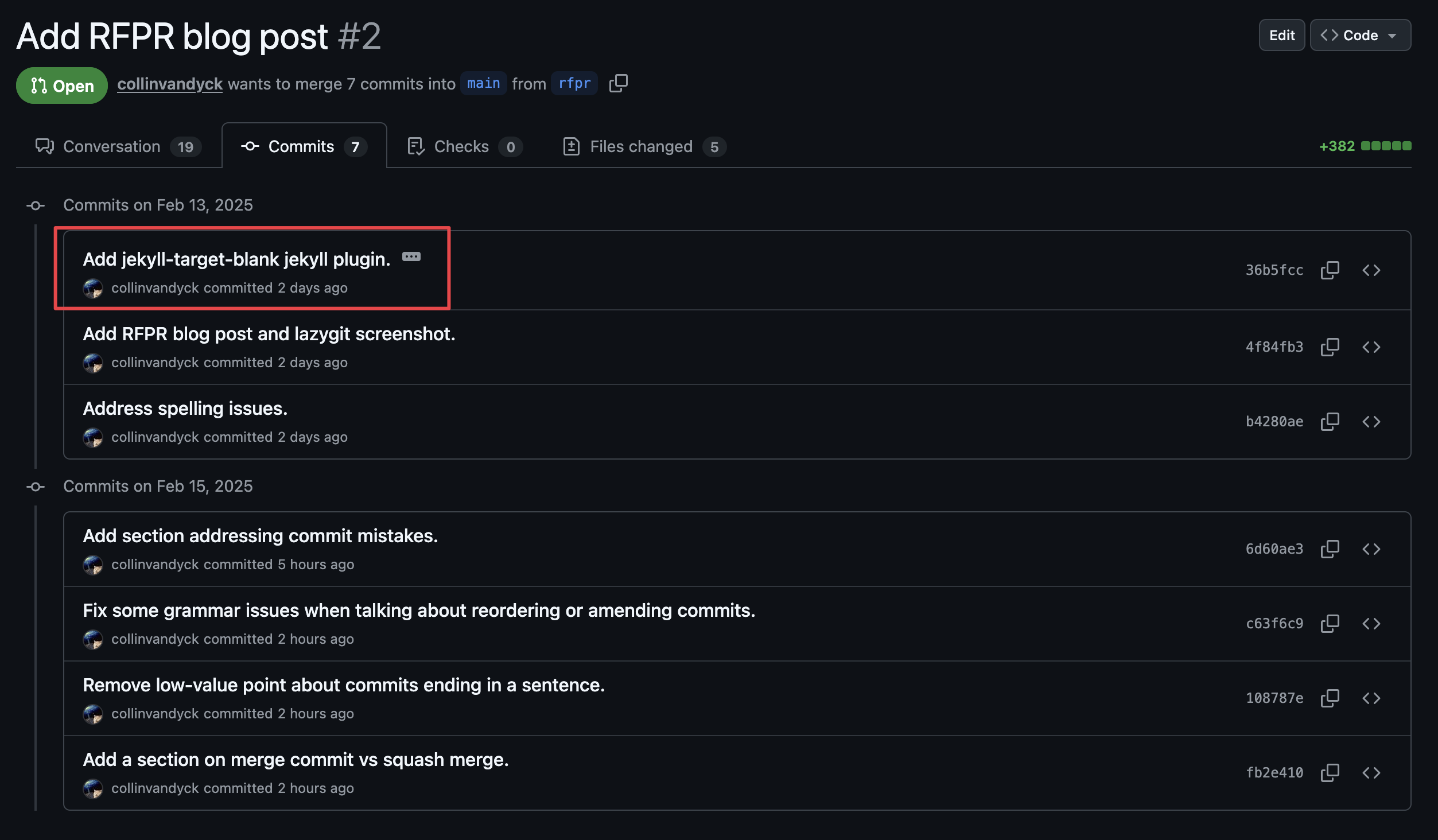

Appendix: Commit Order Reviews

If you’ve never reviewed a PR in commit order, it’s worth mentioning that GitHub makes this a bit easier through keyboard shortcuts. To do this, click the Commits tab on the PR, and then click the first commit:

On the commit interface, you can leave comments as you normally would in the “Files changed” tab.

When you’re done leaving feedback you can use the n and p keyboard shortcuts to go to the next

and previous commits in the PR, respectively. GitHub has more shortcuts detailed in a dialog that

can be opened by pressing ?.

Many thanks to Larry Marburger and Mike Heffner for reviewing ❤️